THE SAN DIEGO UNION-TRIBUNE • SATURDAY OCTOBER 23, 1999

By Devorah Knaff

Photography by Laura Embry

Hair apparent: Six-week-old Joselin Rodriguez gets a checkup.

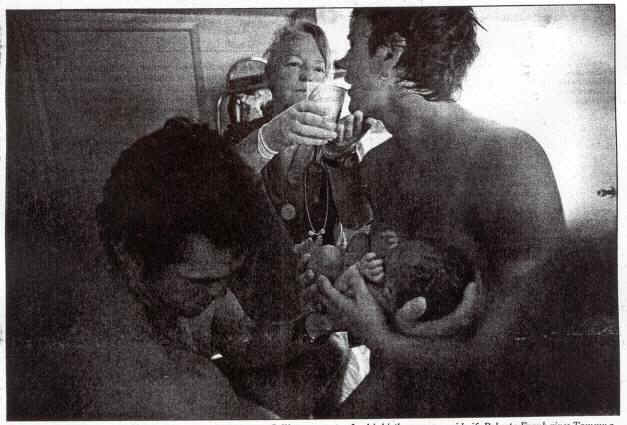

It’s a boy: Derek Finley and his wife, Tammy, hold their son, Collin, moments after his birth, as nurse midwife Roberta Frank gives Tammy a drink of water at the Best Start Birth Center in Hillcrest. Using a midwife, Tammy Finley said later, helped her feel “more in control.

Roberta Frank’s experience with her first child is typical of many women who eventually seek out midwives. “It wasn’t that I didn’t have a good doctor, because I did,” said Frank “But the whole environment of giving birth in a hospital is not a very soothing one. “What I wanted in giving birth was really something that all women want. You want to feel that your emotional needs will be met. “Giving birth is exhausting and painful and it can be dangerous, but it’s also a time of joy. When I went to my midwife (for her second child), I felt that I was being taken care of physically as well as emotionally.” With more women seeking environments where birth is treated as a natural experience, as something that should be celebrated. San Diego’s midwife community is flourishing. And the medical establishment is beginning to embrace a practice once associated with the counterculture.

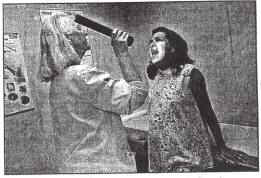

Caring attitude: Roberta Frank checks Rocio Ramirez during a prenatal visit at the San Diego County Medical Center. In addition to helping during labor and delivery, midwives provide a range of health services.

“When I was practicing in the Midwest we had midwives in the hospital, and so it was definitely very different for me when I came to California,” said William Simpson, one of the obstetricians who oversees labor and delivery services at UCSD. “I was used to working only with other doctors and nurses. “But as I’ve gotten used to working with midwives. I’ve come to see that they have a great deal to offer women … that doctors and midwives can serve as complementary health-care providers. We each have something valuable to give to women who are pregnant or in labor.”

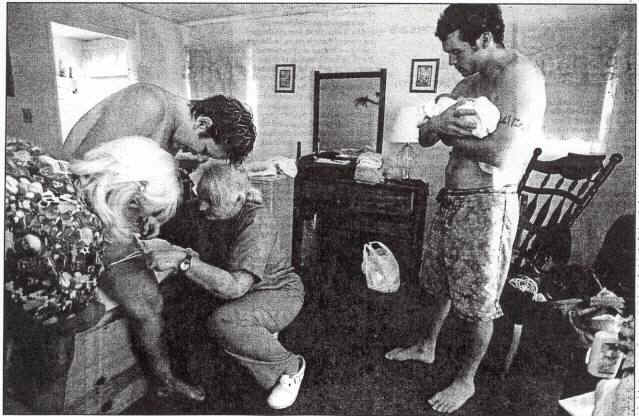

Finishing up: Nurse Anne Allen, (left) and nurse midwife Roberta Frank help Tammy Finley to deliver the placenta while Derek Finley holds his just delivered son, Collin, at the Best Start Birth Center in Hillcrest.

Breaking Stereotypes:

Midwifery still accounts for a minority of births in the United States – but the percentage is rising steadily, according to Lauren Hunter, director of UCSD Nurse-Midwifery Clinical Services. In 1973, 1 percent of American babies were delivered by midwives. In 1989, 3.6 percent of births were performed by nurse-midwives, midwives who have a formal nursing degree and generally help give birth in a hospital or birth center.

In 1996, that figure rose to 6.5 percent, according to Hunter- and these newer figures do not include births performed by certified midwives, midwives who are trained by another midwife (before a 1993 state law took effect, they were called “lay midwives”). They are licensed by a national organization, the Midwives Affiance of North America, and required to have an association with a doctor. “I think that people may have had this stereotype of the kind of women who go to midwives as all being sort of late-blooming hippies,” said Paula Tipton-Healy, a certified midwife in Encinitas who has worked in the field for over 20 years. “But in fact what you see – what I see in my own practice – is that a wide variety of women come to see midwives. A lot of them have had bad experiences with a previous birth and they are looking for a more personal, more caring, more supportive environment A lot of them are concerned that they have some measure of control that they can be equal partners.

“Many of them come from countries that have much stronger midwifery traditions than the United States has, and so it just seems natural for them to seek out a midwife. And some of them are relatively poor women, and the formal medical community has never been as receptive as many would like to the poor. About 10 certified midwives practice in San Diego County, and scores of nurse-midwives practice at the naval hospital, at Kaiser facilities, at clinics and at UCSD. This year, UCSD has begun to allow nurse-midwives not employed by the university to bring patients into its hospitals, a first for Southern California.

Midwifery is essentially the provision of assistance during pregnancy and especially during labor and delivery. This includes everything from giving back rubs and telling a woman how far she is dilated to providing emotional support and suggesting positions that may be more comfortable during labor. They also offer other services, from family-planning advice to gynecological checkups and nutritional counseling.

For American midwives and their clients, midwifery is also an attitude about pregnancy and labor. They approach pregnancy and birth as a natural process that does not usually require high levels of medical intervention or treatment, but rather support and education, according to women who have used midwives. “You could almost look at me as a test-case study, because I had one of my sons in the hospital with a doctor, one with a midwife in a birth center and one with a midwife in a hospital, and the experience was very different each time,” said Lynne Anne Baker, whose children are now 7, 5 and 2 months. “And what I found was that midwives are more supportive. Doctors look at labor from an interventionist point of view. They’re trained to see what might go wrong and take steps to remedy that.”

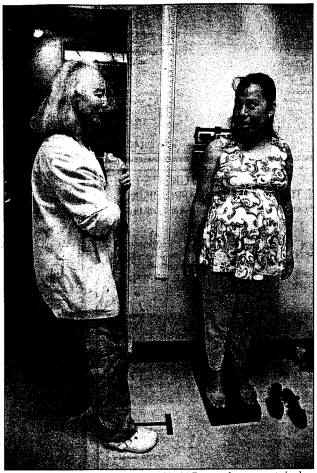

Weighty Questions: Frank reweighs Cintia Reyes, who was surprised she had gained so much weight since her last visit.

Active Roles:

Roberta Frank – who, after having her second daughter, entered UCSD and graduated in its first class of nurse midwives 20 years ago – sees the difference between doctors and midwives as curing vs. caring.

“The doctor looks for trouble,” said Frank. “That’s not meant as a criticism. That’s what doctors are trained to do. That’s what allows doctors to save lives.” But it is also an attitude that is really the most useful when someone is sick, and of course pregnancy is not a disease.”

Frank is now a nurse-midwife at the Best Start Birth Center in San Diego, where her clients and those of other midwives at the clinic are a cross-section of the kind of women who are likely in the 1990s to seek out midwives: well-educated women, poorer women, immigrants, women concerned with taking an active role in the births of their children.

“I’m not sure that we have a typical client,” Frank said. “We have clients who are in their teens and in their 40s, those giving birth to their first child or their fifth, all different levels of education and income, all different races.” One of her clients, Tammy Finley, points to the empowerment she felt when Frank helped her give birth to her two month-old son at the Best Start center. “One of the things that was most important to me in choosing to have a midwife was that I felt that I was much more in control,” said Finley, who also has a 2-year-old son. “When I talk with doctors, they tell me what the procedure is going to be. What they’re going to do to me. When I talk to midwives, they ask me what I want. I am the one who determines what is going to happen to me and to my baby, and that’s very important”

Greater Options: Giving women greater health-care choices was one of the recommendations of a report issued earlier this year on midwifery by the Pew Health Professions Commission and the University of California San Francisco Center for the Health Professions. It urged insurance companies and health maintenance organizations to include a full range of midwifery services in their offerings describing midwifery as an “essential element of comprehensive health care for women and their families.”

This old house: Frank in the renovated house that is the Best Start Birth Center. Photos of children born there decorate the walls.

Health-maintenance organizations have responded, and insurance companies are also more inclined to cover midwifery services than they were 20 or even 10 years ago, according to Bonnie Everett, the chief financial officer for the Best Start clinic. “I think that American women really aren’t aware of the options open to them. I think that a lot of women think that they really don’t have any other options other than to go to a doctor, but of course that’s not true,” said Andrea Melin, Tipton-Healy’s partner at Birth, Babies & Beyond in Encinitas. “And I think that it’s also true that women may think that it’s more dangerous to have a midwife than a physician but that’s not true either.” The Pew notes that in 1994, 24 countries had lower infant-mortality rates than the United States and that in the last 15 years, maternal death rates in the United States have stayed the same despite the fact that half of those deaths are classified as avoidable (and even though 93 percent of births in the United States, according to the report, are attended by a physician).

Still, midwives in the United States have generally not had an easy time, being accepted by the medical community.

“There are a lot of reasons-that doctors have not worked hand-in-hand with midwives,” said Robin DiMatteo, a psychologist at UC Riverside who studies medical institutions and patient-doctor relationships. “In part, its because they risk their malpractice insurance if they do. But it’s also clearly in large part because the two groups represent very different cultures – on the one side a male-dominated, scientific-based group; on the other, a lay-trained, humanistic, female group. It’s not surprising that the two groups would have an uneasy relationship. But what you see now is some coming together of the two groups in the recognition that they both have something to offer women, which is good for everyone. It offers women more health choices and it allows these two groups of professionals to work together and learn from each other.”

Devorah Knaff is a Riverside-based writer.